Housekeeping by Marilynne

Robinson (1980)

Recommended by Stuart

Having

a sister or a friend is like sitting at night in a lighted house.

I spent Christmas in

Oxford, with Kathryn and her family. We played Yahtzee, we drank Lidl’s knock-off (and far nicer) version of

Southern Comfort, we watched The

Manchurian Candidate. Spending the festive season there was indeed like

sitting at night in a lighted house. Lighted with the mini-bulbs on the tree, and a family’s love.

It’s still Christmas (ish).

If I can’t be sentimental now, then when?

I also read Housekeeping. I purposefully kept this

as the penultimate Two Readers book because

I suspected it would be one of my very very favourites. And so it proved.

Anyone that leans to look into a pool is the woman in

the pool, anyone who looks into our eyes is the image in our eyes, and these

things are true without argument, and so our thoughts reflect what passes

before them.

Thank you, Stuart Evers. Here

he is cooking an egg. (He hates eggs).

Why is he cooking an egg

on Battle Of The Pans for charity? Because he’s only an acclaimed novelist with two fabulous books to

the good, Ten Stories About Smoking and

If This Is Home.

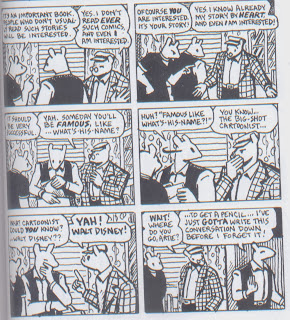

I’ve known Stuart for ages

now, way before either of us had a published book. (Always satisfying to say

you knew them before they were famous, darling). We met during the

post-university social whirl. He was friends with my friends, and a proper looker. I couldn’t fail to notice

someone with his kind of louche grace! The first time I spoke to him properly I

was about 22, and we were at (the now sadly closed) Rowan’s Bowling Alley in

Finsbury Park. Neither of us could bowl but both of us could drink. The former

was quickly abandoned for the latter, and we’ve been friends ever since.

He recommended both Jude

and I fifty-two books to read. What a guy. Jude chose Georges Perec's Things; I decided to

leave my book to the hand of fate. In our modern world, that hand equates to a

random number generator on the internet. Although I promised the generator I

would read Jack by AM Homes, I immediately broke that promise, because I saw Housekeeping at four. I knew that was the one.

(By the way, I’m keeping

Stuart’s list of other novels for future reference. This year has taught me

that I need to be far less sniffy about contemporary fiction. Stuart writes an

excellent blog, and here is his list of this year’s best books. I shall be

delving into that, too.)

Why did mine eye alight on Housekeeping? Partly because I knew it

to be an important modern novel, but mainly because I was fascinated by

Marilynne Robinson’s approach to fiction. Housekeeping,

her first novel, was massively lauded at publication in 1980 and nominated for

the Pulitzer Prize. Gilead, her

second novel, was massively lauded at publication in 2004 and won the Pulitzer

Prize. Twenty-four years and two masterpieces at either end. I have the hugest

amount of respect for people with very high inner critics who will not dish up

anything unless they are sure it’s astonishing.

Housekeeping’s power is stealthy. You

get to know characters as you would in real life: they don’t dump out the

contents of their individual personal history handbag on the table the first

time of meeting. They’re guarded, waiting until they can trust you, sure that

you understand them. And, because you’ve worked to get to know them,

their tragedies become yours.

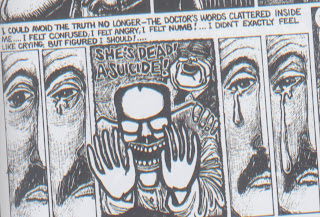

Ruth and Lucille, sisters

and orphans, are well acquainted with loss. Their mother, Helen, committed

suicide; their grandfather perished in a locomotive accident; their

grandmother, after caring for them for five years, ‘one winter morning eschewed

awakening’. They are then passed on to Lily and Nona, another pair of sisters.

Uncomfortable with children, they struggle to relate to the introverted Ruth

and Lucille.

‘That Lottie Donahue could help. Her children are alright.’

‘I met the son once.’

‘Yes, so you said.’

‘He had an odd look. Always blinking. His nails were

chewed down past the quick.’

‘Oh, I remember. He was awaiting trial for something.’

‘I don’t remember just what.’

‘His mother never said.’

Someone filled the teapot.

Lily and Nona aren’t bad

people, they just don’t really want the responsibility of bringing up two

troubled little girls while in their twilight years. They connive to palm them

off to Sylvie, Helen’s sister. Sylvie is a transient, who sleeps with her shoes

under her pillow: an enigmatic woman who few people understand (or wish to). However,

living with Ruth and Lucille brings her a sense of home, and the girls, at

least initially, find solace with her unusual ways.

Not an especial amount

happens in Housekeeping until the

final fifty or so pages, when separation trauma becomes the primary theme. First

comes a deeply upsetting schism between Ruth and Lucille, the latter growing

embarrassed by Sylvie’s unusual behaviour – so much that she is prepared to

forego her sister and Sylvie's defender. Very realistically, Robinson pulls out the hardness and the

pity of how two formerly inseparable people grow apart.

‘It wasn’t the flowers, Ruthie.’

That sounded rehearsed. I waited, knowing that she would go on.

‘It was much more than that. We’ve spent too much time

together. We need other friends.’

It isn’t only Lucille who

views Sylvie as an unsuitable mother figure. The reader has been used to seeing

Sylvie’s housekeeping from Ruthie’s perspective; all of a sudden we see it from

a conventional viewpoint. The final act of Housekeeping

is a quietly harrowing exploration of how alternative relationships and

living situations are seen from the outside. Just as with Robinson’s

characterisation of Lily and Nona, there’s no judgement against the people who

are not comfortable with Sylvie and Ruth’s lifestyle. Although I felt Ruthie

clinging on to Sylvie very strongly, also (and perhaps because I’ve worked in

social care research) I understood also how they could not be left as they are.

Neighbours don’t only stick their noses in because they don’t approve. There is

a genuine, and laudable, desire to protect children from harm. Neglect is the

hardest form of abuse to detect and to stop, and the consequences of not

listening to that voice that says ‘that family down the street are worrying me’

could result in another Victoria Climbie or Baby P.

The book seems to be

called Housekeeping because it looks

at how we keep our homes in order: the domestic chores and the emotional

well-being. Two Readers has been a

sort of housekeeping, too. Reading and blogging on a book a week offers up its

routine, while the critical reflection and heartbursts of love for my friends

has been its emotional ballast.

Housekeeping this blog,

and getting them all in before the end of the year, was something I thought I

could do. I really did. But today my laptop power pack has broken: I've written my final post, Jude's recommendation of course, and I'm hoping the remainder of the battery will hold while I put it up.

2013, you bloody drama queen to the end.