The Weird World Of Eerie Publications

by Mike Howlett (2010)

Recommended by Mike

It was my birthday.

Kathryn directed me to an unlabelled VHS tape.

‘It’s from me and someone

else,’ she said. ‘Play it! Play it!’

I screamed in delight and

threw my arms around her.

‘Turn it off now,’ Kathryn

said, as the title sequence finished. ‘I’m not watching it.’

Cannibal Holocaust, for the uninitiated,

is a notorious video nasty. You can get a flavour of it from this trailer

(NSFW):

Even when considered in

the later context of torture porn films like Hostel, Cannibal Holocaust is

repulsive and intense in its imagery. But, (very unlike Hostel) it has a great deal to say about serious subjects – such as

authenticity, Western anthropological assumptions, media exploitation of

culture, and the abuse of animals. I’d wanted to see this film, (then) banned

and very difficult to get hold of, for years.

So how did Kathryn, who

avoids horror movies at all costs, track down Cannibal Holocaust?

The answer is Mike.

Kathryn and Mike ‘met’ on

an indie-pop message board. I find it utterly brilliant that my first

introduction to Mike was through Cannibal

Holocaust, while Kathryn’s was through songs like this:

Mike is American, and he

and I began writing letters to one another. Through our correspondence, I found

out that he loved horror movies of all eras and styles. My own palate was then

fixated on stylized 1970s Euro-horror and nihilistic American efforts like Last House On The Left, and I credit Mike

with considerably broadening my tastes.

So when I asked Mike for a

book recommendation, he came up with a lavishly illustrated and unapologetically

nerdy history of a gruesome comic book company. What kind of person would write

a book like this?

Mike would. And he did!

If anyone’s thinking Mike

recommended this book to me in order to promote it, I can guarantee that’s the

furthest thing from his mind. I know exactly why this most generous and

enthusiastic of souls sent me this: so I could understand and love the very

weird world of Eerie Publications for myself. If he’d not written this book, he

probably would have shipped me over two dozen original comics instead.

Weird and its clammy ‘the world’s gone to shit’ brand of horror was one of

the few pop harbingers of what was just around the corner.

Weird, along with Terror Tales, Horror Tales, Tales Of Voodoo, Witches’ Tales, Tales From

The Tomb and many other shorter-lived titles, represented the empire of

Myron Fass. Fass, a mixture of opportunistic capitalist and deranged gun-toter,

cut his teeth in the early 1950s horror comics boom. Blood and oddness had run

riot during this period, but it didn’t last. In 1954, the quasi-academic tract Seduction Of The Innocent tenuously claimed

horror comics had a deleterious effect on children, and it ushered in an era of

censorship (‘the code’): the comics’ bloodletting was stemmed, and

unsurprisingly no-one wanted the new neutered stories. Horror comics were over.

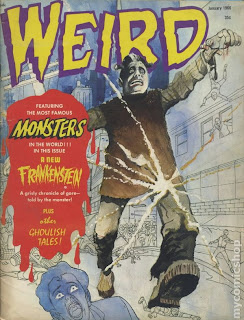

Fast-forward a decade. In

January 1966, this hit American newsstands.

The first Weird reprinted

seven pre-code horror stories […] In some panels, a few extra drops of blood

were added to the original art to make it a bit more gruesome.

Myron Fass had hundreds of

these 1950s horror stories to mine. Once he’d printed ‘em up on cheap paper (with

even cheaper ink that turned a reader’s fingers to charcoal) all Fass had to do

was commission new covers.

And what covers they were:

a sick, wonderful art form in themselves. In this book, Howlett generously

reprints every single one (and the best get their own full-page glory). Check

out the human corn-on-the-cob!

And the meat grinder!

The titles were

successful, and because Fass now had so very many horror comics on the go,

those 1950s stories were running dry. Did he commission new stories? Did he

buggery! The man was allergic to paying for stuff. He went for the cheapest

option: to give the impression of freshness, he got artists to redraw those

same 1950s stories, retaining the original dialogue balloons and text, but with

instructions to gore them up. A new title, and voila: a ‘new’ story.

However, it was this very

workhouse that gave some talented artists freedom. They creatively interpreted

the 1950s material, playing with panels, perspective and character. As long as

they also shoved in an eye trauma or a disembowelment, Fass couldn’t care less

if they indulged their artier side. Finally, even the redraw tactic ran dry and

new stories were grudgingly included, but reprints of the same ancient shit

continued right up to the magazines’ dying days in the mid-1970s.

I think my favourite part

of the Eerie Publications story was the ultra-bizarre short-lived projects. Look at the mixture of Lady Gaga

and Fantastic Planet that was Gasm, from November 1977…

…and the obligatory Star Wars cash-in with amusing copyright-dodging name!

There was even a magazine on the Swine Flu epidemic of 1976! Was there nothing this man couldn't exploit?

I’m so made-up for Mike.

This book is a brilliant achievement. With specialist geeky subjects like this,

the writing is often stale, but that’s not the case at all with The Weird World Of Eerie Publications.

Mike is as funny and lovely in print as he is in real life, and I’m really

proud that he’s my friend.