Blaugast: A Novel Of Decline by

Paul Leppin (c. 1933)

Recommended by Harry

There are two styles of

books that majorly push my buttons.

Number one: a hefty, often

depressing, English Victorian novel.

Number two: a brief,

always depressing, European novel of the interwar period.

When I asked my friends

for their recommendations, the request came with just one coda. ‘Please don’t

make it too long,’ I said in various pubs / texts / emails. ‘I do have to read

it in a week.’ Of course, a few chose to ignore this request and recommend me

doorstops anyway (albeit with some cute justifications, e.g. Lizzie: ‘It’s five

books, yes, but they are children’s

books’; Geoff: ‘It looks thick, but

on some pages there are only a few words’; Barry: ‘Well, at least I’m not

recommending you Ulysses’). Anyway, I

wasn’t expecting (and I didn’t get) any lengthy Victorian novels. But I was

hoping to get at least one succinct slice of degenerate continental misery.

Are

you interested in catastrophes?

Always.

Blaugast: A Novel Of Decline is the

final novel of the Prague German Paul Leppin. Unlike his near-contemporary Franz

Kafka, there has been little posthumous celebration of this author; Blaugast, unpublished at the time, is

still a very niche work (this edition, the first commercial English

translation, is from 2007 on a small Czech imprint). I’d certainly never

heard of Leppin, and he seems unknown to even the keenest readers of European

modernism.

This is a terrible

literary injustice. For my money, Blaugast

ranks as one of the lost masterpieces of Mitteleuropa.

Engulfed by disasters, which he sought in vain to

understand, he found himself hopelessly adrift, surrounded by an enemy that

no-one ever called by its name. But its presence was irrefutable and cruel. It

made itself known in faltering discussions, ejaculations, and dissolute jokes,

in the cracks of doors and within the corners of rooms.

This is our anti-hero, Klaudius

Blaugast. A directionless middle-aged clerk, at the start of the novel he randomly

meets an old schoolfriend, Schobotzki. What, Blaugast cheerfully asks, has

Schobotzki been up to since school?

‘I’m going to seed,’ he said casually. […] ‘It has to do

with the research I’m involved in.’

Blaugast, intrigued,

follows Schobotzki to his ‘laboratory’ where he meets Wanda.

Her eyes, serenely cold, flickered like a candle’s flame

just before its death.

Prostitute and emotional

sadist, Wanda soon brings Blaugast under her powerful influence. He is

directionless no more. He becomes obsessed with Wanda and performs ever more

humiliating acts upon his own body and psyche. Physically, it leads to syphilis;

socially, it leads to financial ruin and homelessness; psychologically, it

leads to complete debasement.

A novel of decline,

indeed.

Yet Leppin does more than chart

one person’s degradation. His unflinching portrayal of wider society mercilessly goading the fallen man is an

equally strong (and even more morose) aspect of Blaugast.

The spastic goosestep of his uncontrollable legs, the

result of the disease now consuming his spinal cord, his face, altered by the

rigid dilation of his pupils, and the solemn rags he preferred as his wardrobe,

earned him the moniker ‘Little Baron,’ which he would acknowledge with an

awkward bow. The epithet was most commonly used by the children who ran behind

him and by the habitués of the beer gardens and pubs, who welcomed the patient

beggar with jeers and jokes.

Leppin particularly singles

out the malice of the bourgeoisie. Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good And Evil that all high culture is based on cruelty*, and

perhaps Leppin is making reference to this. Leppin’s gloomy point that everyone

has a propensity for sadism as long as the victim is socially marginalized is

well made via one especially ugly episode. ‘Little Baron’ has been beckoned

into a wine bar.

After downing a few glasses of schnapps given him, he was ordered to

masturbate onto a plate in the presence of all for the succour of a meagre fee.

I’ve quoted from this book

so much because Leppin made me gasp on every page with his inventive prose. Look,

look, at how he describes

nervousness:

A rat’s tooth, voracious, bespattered with carrion,

gnawed at his intestines.

If I ever wrote a sentence

like that, I would just stare in the mirror for about a week, grinning at my

own brilliance.

This is my second

favourite book of the project (after The Underground Man). But unlike The

Underground Man, which I’m sure everyone who reads this blog would enjoy,

I’m far warier of pushing Blaugast on

people. Although there is some redemption within, it is nevertheless a pretty

nihilistic work, and certainly the kind of book you have to want to read. Next year I will explore

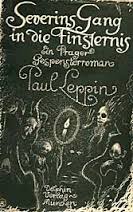

the other works by Leppin: Severin’s

Journey Into The Dark sounds incredible!

I’m interested in hearing

of how Harry acquired this particular taste and discovered Blaugast.

Because, really, I know

hardly anything about Harry, other than the reason why I asked him to

contribute to Two Readers: that he

has excellent taste. (Oh, and that he’s a prominent academic, and that two days

ago he viewed the house of a former member of Brit girl group The Paper Dolls).

He got in touch with me following Seasons

They Change, we’ve nattered over social networks, and had one abortive

attempt to meet up (trains and overrunning appointments stymied us).

I hope in the future our

luck will hold for some facetime. It has to: I feel that, as time goes on, we

are just stockpiling the many, many, many things we have to discuss. I’ll leave

you with just one of them.

*N.B. I know I sound pompous

here. However, my knowledge of this Nietzsche work comes entirely from Kevin

Kline’s character in A Fish Called Wanda.