The Picture Of Dorian Gray by

Oscar Wilde (1891)

Recommended by Nicky

FOREVER YOUNG

FOREVER CURSED

Not the words of Oscar

Wilde, funnily enough, but the tagline to the 2009 flop Dorian Gray, starring Ben ‘Who?’ Chaplin.

I’ve been trying to source

my Two Readers books from Sheffield

libraries as far as possible. That’s why I read a large-print The End Of Mr. Y and lugged around the Rabbit Angstrom Tetralogy. We must borrow from them: it is one way of

standing up to the cultural desecration this government is wreaking. Fuck them and their assault on free and

accessible books for everyone.

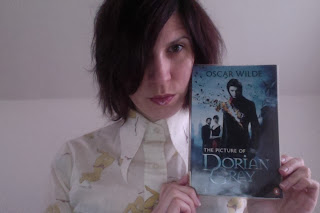

So that's why I'm holding up the

already-dated film book jacket version of The

Picture Of Dorian Gray. Always makes one look serious about classic literature.

Still, in my case it felt appropriate. My introduction to The Picture Of Dorian Gray came at age

13. The 1945 film version (starring Hurd ‘Who?’

Hatfield) was the afternoon ITV matinee.

That film blew my tweenage

mind. I knew of Oscar Wilde – Morrissey went on about him, and he was always

the answer to quote questions on Going

For Gold – but I didn’t know much of The

Picture Of Dorian Gray. I found the story beguiling, and the one-liners

killer; plus the film itself seemed very inventive. It was in black and white,

but whenever it showed Dorian’s portrait, it switched to fantastic

technicolour. When I saw the final, degenerate painting, I gasped in horror.

(It’s here, but for the full effect I’d recommend not peeping and seeking out

the movie instead).

I read the book shortly

afterwards. Not much can compare with experiencing Oscar Wilde at that age.

Wow. Who were these waspish

sophisticates with an aphorism for every mood? I really thought I might become

Lord Henry Wotton as an adult. Never mind that I was in some crap area of

Norwich, and my day involved thinking up excuses to get out of cross-country running rather than flirting with duchesses and renaming orchids.

I was in the gutter but, yes, I was looking at the stars.

He was amazed at the sudden impression that his words

had produced, and, remembering a book that he had read when he was sixteen, a

book which had revealed to him much that he had not known before, he wondered

whether Dorian Gray was passing through a similar experience.

Nicky said that The Picture Of Dorian Gray meant a lot

to him when he was growing up. I think it’s one of those special texts: key in

forming a persona, or at least key in forming an ideal of what we’d like our persona

to be. And, in Nicky, I can definitely see its influence.

Exhibit one: wit. Every advent Nicky

counts down his ‘sexy boys’ chart. His type isn’t really my type (Jedward got

in there!) but his commentaries make me cry with laughter. Last year, when

talking about some actor no-one’s heard of (Ben Chaplin? Hurd Hatfield?), he

wrote ‘He always seems to get in the lower reaches of the chart. Much like All

About Eve singles in the late 80s.’

Exhibit two: sociability.

An absolute joy to be around. We’ve started a semi-regular cinema club!

Exhibit three: disinhibition.

Open and honest about all sorts of stuff – from sexual behaviour to Eurovision fan

politics – he’s prompted me to think about relationships, sex, identity, and

celebrity, in myriad different ways.

He’s far more

Lord Henry’s heir than I am. Damn it.

‘Believe

me, no civilised man ever regrets a pleasure.’

It’s interesting to

(re)read a book whose plot is so well-known in popular culture. The shorthand –

vain pretty boy makes a Faustian pact that his portrait, not he, will age, and

then goes on a massive debauchery binge – is pretty much what happens. But, as

with any distillation, it conceals as much as it reveals.

Reading The Picture Of Dorian Gray as an adult, I found it to be a very sad

novel. It is as much of an unapologetic ode to hedonism as Crime And Punishment is a sanction for the cracking wheeze of

murder. Dorian is a paradoxical character. He is, at once, amoral and virtuous;

a manipulator and a naïf; an anti-intellectual and a nerd. The lovely young

Dorian, at the start of the book, is somewhat laconic and petulant, but

absolutely magnetic. Hell, anyone would fall in love with him.

He does not stay so pure after

he meets Lord Henry. Henry is an endlessly quotable bon vivant, and Dorian seeks to be both what he thinks Henry will

desire (a young and beautiful man) and what he thinks Henry is (a pleasure-seeking wit). The pair

enter into a Henry Higgins-Eliza Doolittle relationship, the key dynamic of the

book; and it is Henry’s speech on how youth is the only thing worth possessing

that prompts Dorian to strike his fateful bargain.

Henry gives Dorian a present.

It was a novel without a plot, and with only one

character, being indeed, simply a psychological study of a certain young

Parisian, who spent his life trying to realise in the nineteenth century all

the passions and modes of thought that belonged to every century except his

own.

Ah! That’s

bloody well À Rebours! I can’t believe how that book

has followed me around this year. Although Wilde never names it, it’s such a unique

work and once read, it’s easy to recognise any allusion to it. Chapter Eleven

is almost completely given over to a parody (or an homage) to the narrative

style of À Rebours, as Dorian meditates on his

possessions and what they represent.

The King of Ceilan rode through the city with a large ruby in his

hand, at the ceremony of his coronation. The gates of the palace of John The

Priest were ‘made of sardius, with the horn of the horned snake inwrought.’

So yet another reason why

I’m glad to have read À Rebours; I’m sure I would have found this

chapter entirely head-scratching if not. Let’s have another picture of it, with its English title, to

remind you to read this incredible work.

As the Henry-Dorian

relationship progresses, its initial teacher-pupil aspect becomes far less

straightforward. Although he wants to emulate Henry, Dorian is simply unable to

do so. People love and indulge Henry, and when he is outrageous, it only serves

to enhance his standing. Dorian, though, is different; he can beguile like no

other, but once his initial charm impact wears off, he is seldom a popular

presence in a gathering. He doesn’t have the élan of Henry – he’s too brooding, too conflicted, and his secret

picture drags after him like a beached whale.

What is left to Dorian? Drugs.

Sex. Material goods. Cruelty for the sake of feeling momentarily powerful. Looking

into the mirror at his never-changing appearance. And all this makes society

dislike him further. I found it fascinating how Dorian’s behaviour becomes more delinquent the older he gets: the amoralist,

manipulator, and anti-intellectual win out, but in a very joyless way.

In life, this is rarely spoken of, but it rings true. While younger, we may be

afraid of consequence: age brings a new fuck-it-ness. Plus, if we do something

exhilarating once (perhaps without exactly intending to) then we learn we can,

and are far more likely to do it again. Yet, with each repetition, our

tolerance grows, and the taste of transgression becomes blander.

Dorian and Henry are the

headline acts in this novel, and I could see why each was so enticing to me at

a younger age. But, reading now, it is the portrait-painter, Basil Hallward, whose

tragedy struck me the most. In love with Dorian from the very start of the

book, Basil watches his beloved muse get sucked in to a new life, and you can feel

every jagged shard of his broken heart.

He drove off by himself, as had been arranged, and

watched the flashing lights of the little brougham in front of him. He felt

that Dorian Gray would never again be to him all that he had been in the past.

Life had come between them… His eyes darkened, and the crowded, flaring streets

became blurred to his eyes. When the cab drew up at the theatre, it seemed to

him that he had grown years older.

It is Basil Hallward who

is really Dorian’s picture. He is the one who bears the scars – as it says

above, even grows older – as a result of Dorian’s behaviour.

And that’s why I found this

book so poignant. Basil Hallward’s suffering is what happens in reality. When

we’re cold-blooded or thoughtless, deliberately nasty or uncaringly selfish,

the distorted mirror held up to ourselves is not a grotesque self-portrait. Rather,

it is painted on the flesh, on the memory, on the very soul, of each person

that we hurt.