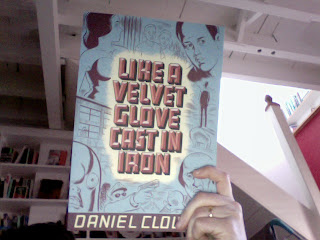

Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron by Daniel Clowes (1989-1993)

Recommended by Kristian Besley

After this week's recommender Kris read my post from last week – about Jonathan Raban's book, Coasting, irregular readers, read down for more – he was worried that he'd picked a book that wasn't deep enough.

Then I opened Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron.

This featherlight, wishy-washy, silly comic Kris had picked for me was actually... I'll pause for an intake of breath here... a series of interconnected stories named after a line from Russ Meyer's Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! about a strange young man, a God-like drawing called Mr Jones who was tattoeed on feet and hidden on moles, a girl called Tina who looked like a potato conceived through an encounter with a mysterious creature who came from the sea, brutal cops, dogs without orifices or faces with maps on their backs, Hitler living in Mexico, a little girl who writes scripts, and a worldwide gender war.

Just like an issue of Bunty, in fact.

But that's Kris for you – putting himself down when he shouldn't. Kris is great. We've been friends since tertiary college, when he had purple hair and a beard and once let off a second world war air raid siren in the canteen... or at least my memory tells me that he did. (That's one of those situations you swear your brain has concocted on its own in a moment of madness). He was in a band called Ken though, a sort of mad-comedy band very much of the early 1990s, who had a cassette album called Unplugged In Llansamlet with a photocopy of a Barratt home pasted on the front of it, and had a song about Carl Cox, and many others with swear words in them which I won't repeat as he's a very grown up, and indeed upstanding, father-of-two now. The purple hair has gone too, I'm sorry to say.

Oh, Kris also played a massive part in my musical education, introducing me to the early works of Gorky's Zygotic Mynci and the music of Orbital, which I talk about on another blog post here. And he was in a band called Grümp – note the umlaut – for whom I made some badges using Tippex and biro. GLORY DAYS.

But back to Daniel Clowes. I knew a bit less about him: that he was one of the artists that helped popularise alternative comics in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and that he'd done some work for the brilliant Hernandez Brothers' Love And Rockets series. I'd also read Ghost World already, and of course seen the film starring Thora Birch (what happened to her?) and Scarlett Johanssen (ah what happened to her), having been a young person in the late 1990s/early '00s of an indie persuasion.

I'd loved both, but I'd not read anything else by Mr Clowes. Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron, I discovered, is definitely not Ghost World, although I really enjoyed it, despite not really understanding what the hell was going on in it.

The best way I could describe this graphic novel is that it's a lot like Twin Peaks in narrative style and tone – although its subject matter feels much murkier. For instance, there's a peculiar old movie at its heart that Clay sees in a dodgy porn cinema, and I felt the ghost of One-Eyed Jacks and Audrey Horne all over that. Still, the first instalment of this series was written at the same time as David Lynch was writing Twin Peaks, so they didn't overlap. Maybe there was just something (really weird) in the air.

Sex, violence, death and dread: boys and girls, they're all here. And God, you feel them. You really understand Clay trying to make sense of some of these worlds desperately, while settling for others co-existing. When he's trying to find out the importance of Mr Jones, you feel his hunger for knowledge deeply; when the little girl he's watching is given her own voice, I felt genuine fear. There are lots of minor characters that recur too, and tons of surrealistic twists...for example, there's a moment when Clay takes a drink, then in the next panel, he and his friend are alien shapes...but even weirder than that. And the dogs without orifices. ARGH.

At points, this book made me think of the late '60s film Performance which I watched over the weekend too. Both are defined and directed – or indirected, rather – by psychedelic leaps. But I liked this book more, as it hinted at something weirder at the heart of us. My favourite bit of all was when the folk song Barbara Allen crops up towards the end, and Clowes uses it, in a way, to try and tie all his disparate, wayward threads together. Things don't end well, but then again, some things don't. This is a book I need to return to, and unpick, and spend hours poring over, just like those cassettes made for me nearly twenty years ago by a teenage boy with purple hair, from an old friend who will always, somehow, feel like a new one.