Nausicaä Of The Valley Of Wind by Hayao Miyazaki (1982-94)

Surely, from dedicated followers of The Fast And Furious franchise right through to Man With A Movie Camera silent film bores, all are charmed by Ghibli’s fantastical worlds. It annoys me that any shit romcom is branded a ‘feelgood' film, for it devalues something like Spirited Away: cinema that is gloriously enjoyable, yet undeniably profound.

In the early 1980s, Hayao Miyazaki,

Studio Ghibli’s founder, pitched a movie about a pacifist young princess living

in a world beset by environmental disaster. However Miyazaki, still largely

unproven as a director, was told that he needed a manga series to secure

funding for this pet project. The argument ran that animated movies based on manga

did far better at the Japanese box office than did original stories.

What did Miyazaki do? Churn out a straw

manga to please the money men? Or create a ridiculously intricate and

multi-layered epic that ran for twelve years?

Set centuries in the future, humanity is

on its knees. The industrialist societies of today pushed the earth to its

limit. Unable to endure the devastation any longer, the earth roared, creating the

Sea of Corruption. This is a vast forest where poisonous spores emit clouds of

deadly miasma, and in which mutated and very angry insects dwell. Since the Sea of

Corruption is uninhabitable, humans are relegated to its periphery, and then divided

into semi-feudal autocratic states. The two primary powers, the Dorok

Principalities and the Torumekian Kingdom, are perpetually at war – ostensibly

over scarce resources, but there’s quite a bit of old-fashioned belligerence

involved, too – while the smaller states are caught in the crossfire. Both

Dorok and Torumekia use deeply unethical military strategies: biological

warfare, racist inflammation, genetic engineering, and implied rape.

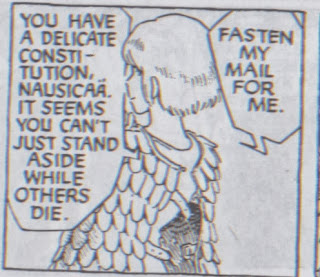

One of these small states is the Valley

of Wind. Nausicaä is its

beloved princess; she is a pure-hearted young girl who has a unique affinity

with the earth. She is even able to communicate with the most feared of all the

Sea Of Corruption’s insects, the giant Ohmu. Nausicaä could easily be an annoying do-gooder, but her characterisation is

superb: she feels real anguish for human, animal and environmental suffering,

while sometimes forced into making dubious moral decisions.

One of these dodgy

compromises is her alliance with the Torumekian princess, Kushana.

Nausicaä and Kushana share a complicated and

fascinating relationship, almost as if they are obverse and reverse to one

another.

Kushana was very much my favourite

character. A brilliant tactician, ruthless and brutal when necessary, she

sprung from a ‘nest of vipers’: a group of ambitious siblings fighting in Roman

internecine style for (often short-lived) supremacy. The brief insights we gain

into Kushana’s family are among the best panels in the whole manga. How far Nausicaä influences Kushana (and, more subtly, vice

versa) is a tremendous tension in the story.

Nausicaä

is in four volumes, and a real Gordian knot: it would take paragraphs

and paragraphs to effectively explain the story alone. And its philosophical

scope is even grander, for it examines different government structures under

extreme crisis. As well as Classical history and myth (Nausicaä

herself was based upon a Phaecian princess in The Odyssey), I detected influences from pre-1914 Europe, primarily

the crumbling Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires. Although my Japanese

history is shaky, its Samurai era seems another key reference point. Miyazaki

seamlessly links all this with modern theories of environmental destruction,

feminism, the abuse of religion, and ethnic scapegoating. Sometimes Nausicaä is about

nothing less than what it means to be human, especially when we have devastated

the means of sustaining our humanity. Its ambition is as enormous as the Sea of

Corruption itself.

The manga was a huge

commercial and critical success. Thus, Miyazaki

had no trouble getting funding for his movie, which was released in 1984.

It is far, far, far simpler work. Although it’s a good film, it’s on to a hiding to

nothing after one has expended the hardcore concentration required to tackle

the manga. The world, for once, should be grateful to cautious investors for without them this movie is all we

would have.

Similar to my previous graphic novel recommender, Alex is a brilliant artist herself. This is my favourite of

her drawings: Kirsty MacColl sitting on her bench in Soho Square, created for

the board game Soho!

She is also a respected film academic and a very good friend. I remember when I first met her about ten

years ago I really didn’t know what to make of her – she was so different to

anyone I’d ever, ever, ever encountered

before. I soon realised what providence was telling me: that she was awesome

and we should get on with this friendship lark immediately. She is extremely

intelligent, highly sensitive, beautifully dressed, and incredibly magnetic. At

Kathryn and Rupert’s wedding someone thought she was a film star.

I love things like Nausicaä, which trust you to hold masses of plot and character threads in your head, and then reward you a million times over for paying attention to them. If I may return to that awkward portmanteau word: feelgood. I feel good to know art has such vision, and I feel super good for knowing that I’ve been able to drink deep from its well this week.

I love things like Nausicaä, which trust you to hold masses of plot and character threads in your head, and then reward you a million times over for paying attention to them. If I may return to that awkward portmanteau word: feelgood. I feel good to know art has such vision, and I feel super good for knowing that I’ve been able to drink deep from its well this week.