Maus by Art Spiegelman

(1980-1991)

Recommended by Matt

The Holocaust.

How can art deal with it?

Talking or writing about

The Holocaust, even in a low-key blog such as this, is a fraught experience. It

feels, especially as a non-Jew, that I must instantly qualify myself: state upfront

about how enormous it is, that it is a unique event, how we must never forget.

This says

more about the author than it does about The Holocaust. Doesn’t every

thoughtful person, who’s not an idiot or a bigot, know that it is an enormous

unique event that we must never forget? Yet, still, I introduce Maus this way. My own fear of being seen

as, at best, a Vichy France (and at worst an Adolf Hitler) if I don’t is too

strong. But the risk, when we expend our

energy and words in repeating such indisputable statements, is that we don’t afford

the event much, or even any, complexity. That our own neurosis hobbles the

ability for analysis, and we end up with a piece of writing that browbeats the

reader with banality.

With tragic irony, it seems

that in more recent times – The

Reader, and the critical rehabilitation of Nazi

filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl spring to mind – fictional and real Nazis have been afforded that

very complexity (and even sympathy). Compare this to The Boy In The Striped Pajamas. I was really quite angry when I saw

this movie, for it was so very saccharine. I asked myself, is such colourless characterization

of those in the camps, as so unrealistically angelic and always seen from the outside, actually damaging? Does it simply reinforce the 'them and us' rhetoric used by the Nazis?

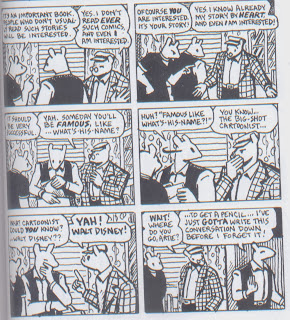

Maus is the story of Vladek Spiegelman,

Art Spiegelman’s father: not only does it narrate Vladek’s Holocaust experience, but also his current life as an older immigrant man living in America, his (difficult) relationship

with his wife Mala, and his attitude to Art and Art’s comics. Vladek’s numerous

quirks and flaws may have something

to do with The Holocaust; or they may just be who he is. The first challenging

concept of Maus is that not every

disagreeable trait in a survivor’s personality is a result of The Holocaust.

Vladek, a Polish Jew,

marries Anja (Art’s mother) in the mid 1930s. Anja is from a wealthy family and

the couple has a good lifestyle, although Anja is vulnerable to bouts of

depression. Vladek tells us of how life began to get difficult for Polish Jews

at the outbreak of World War II. What is most striking about the first book of Maus is not in itself the shrinking sphere that Jews are forced to function in

(via seizure of businesses and property, and the acts of violence and murder):

these processes of discrimination by the Nazis are well-known. But Vladek’s

story brings an insight into the ad hoc nature

of this time, so different from the image of steely calculating Nazi enforcers.

Sometimes Vladek would be released when he was clearly committing an

executionable offence, but sometimes he or the family would suffer with not

even a thin excuse given. This inconsistency (while clearly on an overall curve towards genocide) creates both

looming dread and grim pockets of hope.

The reader is able to root for Vladek: he does not allow himself to be a victim

easily. He works hard, he is clever and resourceful, he has wealth to exchange

for favours, and he is prepared to hide or collaborate when necessary.

But Auschwitz was the

fate for over one million Jews, and so it is for Vladek. Book Two of Maus concentrates on Vladek’s time in the extermination camp. Vladek mentions little of the gas chambers (it’s not from ignorance: all the

prisoners know that they are there, and that they are used), but rather he

concentrates on the day-to-day: the hunger, the lice, the relationships with

camp supervisors, and the cumulative effect of smaller humiliations.

We learn Vladek’s story as

Art learns it: with digressions, arguments, and frustrations. The present-day

Vladek is extraordinary. He throws away Art’s trendy coat and gives him a

horrible old one of his to replace it; he returns half-eaten cereal to the

store (‘The manager helped me as soon as I explained to him my health, how Mala

left me, and how it was in the camps’); he fakes a heart attack to get

attention; he thinks all black people are thieves. At times, Vladek is so difficult that Art worries he is

actually stereotyping Jewish people as miserly and intolerant, thus giving fuel

to Nazi sympathizers.

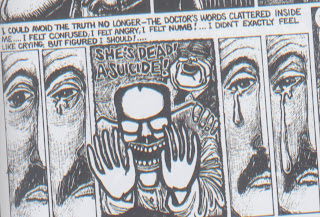

We hear of, by the process

of creation, the author’s own upbringing and history. His mother, Anja – who

also went to Auschwitz and survived – killed herself when Art was twenty.

Spiegelman wrote a frankly amazing short comic strip about it in 1973, Prisoner On The Hell Planet (reproduced

in Maus).

The strip is a piercing

scream of grief: we are left to wonder how far Anja’a suicide was a legacy of

Auschwitz, how far it was her own depressive nature, and how far it was her

unhappy familial relationships. She kept diaries but, to Art’s fury, Vladek

threw them out. We only ever know of her through Vladek and Prisoner On The Hell Planet. But, yet, Anja

haunts Maus: she glides between the

frames, whispering her own story.

The other highly original

thing about Maus is its use of animal

metaphor. The Jews are mice; the Nazis, cats; the Poles, pigs; the Americans,

dogs; the French, frogs. Spiegelman’s metaphors initially seem to say that we

are not all just the same people

underneath our racial and national identities: that they define us, and so far

so that they manifest in fundamental differences as strident as those found

between animal species.

However, by emphasizing

difference rather than minimizing it, Maus

highlights the philosophical claptrap that The Holocaust drew oxygen from.

If you’ve ever had the misfortune to read any of the mouth-foaming ‘theorists’

Hitler subscribed to, or any of Mein

Kampf itself (which is so muddled it’s like slogging through hateful wet

cement), you’ll know that these texts might as well be saying cats should get

pigs and frogs to collaborate with them in order to kill mice. That’s how

logical they are. At the same time, through using cats and mice especially,

Spiegelman is able to visually evoke the power relationship between Jews and

Nazis, and also to refer to, and undermine, the Nazi propaganda that equated Jews with rats (as seen in 1940's The Eternal Jew).

An incredibly important book, this, I think. And, still, within it, there is room for laughter. Not hurtful or ambiguous dark laughter, but real, beautiful big belly laughs.

Matt and I were born

within a few days of one another. There’s something quite lovely about meeting

someone of your own school year when you’ve left your childhood behind. We have

very similar cultural tastes: Kate Bush, All About

Eve, RuPaul’s Drag Race, Robyn, Love And Rockets… and it’s not only what

we like, but how we like. There’s a

lot of geeking about b-sides and quoting from scripts.

But, as with all friends,

shared taste only gets you so far. Extremely caring, he works in HIV prevention

and awareness, and his efforts helped the campaign The HIV-Hop win a national award last year.

PLUS he’s a talented artist, and is prolific without compromising on quality –

that in itself is an inspiration to me. Matt, with his artistry and his

kindness and his passion, well, he makes me feel that I can weather any shit, and then come out of it with a

Bette Davis hair-toss.

I’m unsurprised that Maus is one of Matt’s favourite books.

He is moved by oppressive circumstances, and despises any form of prejudice:

but he is uninterested in simply doling out platitudes. And that’s the essence

of Maus.

I want to understand The Holocaust. But that doesn’t mean that I can understand The Holocaust.